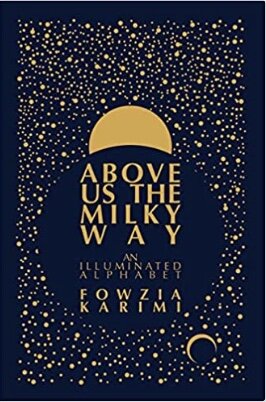

Above Us the Milky Way by Fowzia Karimi (Deep Vellum Publishing)

Near the end of 2020, a bookseller pulled this book from a shelf and showed it to me. Everything about it was beautiful: the gold dots on a deep blue unjacketed cover, the weight of the paper as I leafed through its pages, its typeface, the way that it used photographs and drawings in a way that seemed part of its text. I turned back when I was two miles away from the bookstore and brought it home, with no real sense of what it was about. I wasn’t even sure that I would ever read it, but the sight of it on my table made me happy.

Two weeks ago I picked it up and began to read, an experience so weighted and rich, so rooted in horror and loveliness that I made my way through it slowly, every day. When I finished it, I pressed it hard against my chest in an involuntary gesture that wasn’t a hug; it was an attempt to make it part of me in a physical way, as it had already claimed my heart and my imagination.

Is this a novel? Is it a memoir? Fowzia Karimi teases with those questions, claiming it is neither one. It is, the subtitle says, An Illuminated Alphabet, one that Karimi says should be read in a random way, not as a linear narrative. Within the order of the alphabet, each letter forming its own chapter, an illumination casts its beam upon the magic of childhood and the cruelty of war, upon the nature of memory--where it lives and how it is revealed--upon the way in which lives are lived in two places at the same time.

If there is a narrative, it’s circular, tracing the journey of a family with five daughters who left Afghanistan for the United States when the girls were quite young. But there is no arc, no resolution, no named characters. There’s Father, Mother, the sisters, and a multitude of family members who were left behind, living and dead.

In their new country, the sisters are one as much as they are five: the sister who sleeps, the sister who walks through the night, the sister who dreams, ths sister who gives, the sister who who loves the sea. Their faces are seen only dimly in family snapshots; in drawings of them only the back of their heads are given. Karimi herself, in her author photo, shows only the back of her head and shoulders. And yet through their memories and their dreams, the games that they play and the chores that they do, they become visible, girls who are both wild creatures, exemplary daughters, creative beings, and nomads by blood and through practice.

Anchored by stories and memories, the family lives outside of the present because they know they could return to their first country at any moment. They have no future because the war has devoured everything they’d known in the past. They live “between what had been and what might have been.”

What they know about the events within the country they no longer live in is terrible. The stories of the dead live within the sisters: those who were buried alive in pits, those whose bodies were tortured, those who were cut in half by gunfire. The girls know and live with these histories that co-mingle with their memories of balloon-sellers, fruit vendors, festive birthdays with tribes of cousins back in their first country.

Karimi’s goal is to “explore the correspondence on the page between the written and the visual arts.” Her small paintings bring objects into the text: a butterfly on one page, a severed finger on another, all rendered with the careful lovely attention of a botanical drawing. Like signposts, they keep readers from growing numb. They and the words that they accompany keep us awake, keep us alive, keep us connected to what we might not ever know, what we might prefer to ignore; the complex and knowledgeable life of children, the bright and bloody history of a country that has long lived with “fire in the sky, limbs in the trees, blood in the streets.”~Janet Brown