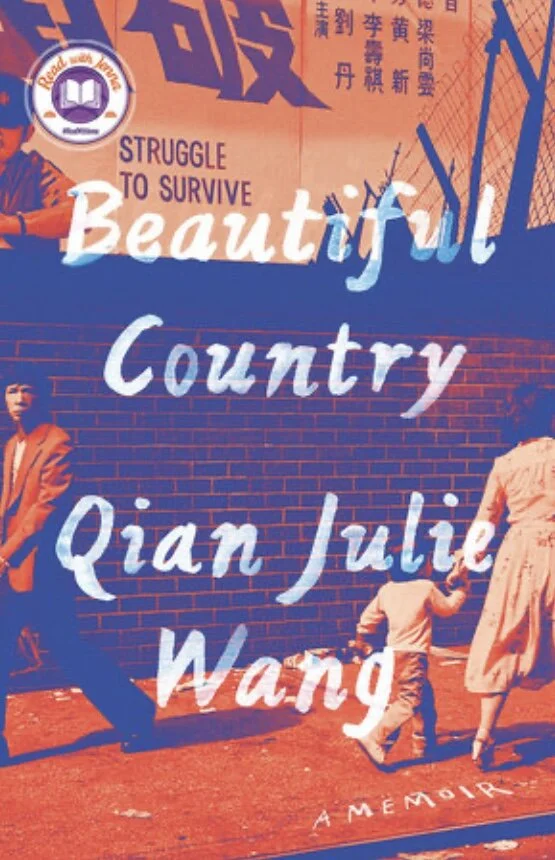

Beautiful Country by Qian Julie Wang (Doubleday)

“My story starts decades before my birth.” Qian Julie Wang’s opening sentence immediately launches a searing memory that is not her own: the story of her father encountering his first dead bodies, corpses hanging from a tree, when he was four years old. Three years later he witnessed the public beatings of his parents during the Cultural Revolution and faced daily humiliation himself at school, where he was singled out as a member of a “treasonous family.”

He grew up to be a professor of English literature, with a wife who was a professor of mathematics. They cherished their only child, and Wang’s father was a constant source of humor and delight to his little daughter. But he carried scars from nis childhood of brutality and fear. He left for America, Mei Guo, the Beautiful Country, with Wang and her mother following him there several years later.

“I ascended to adulthood at cruising altitude,” Wang says, when her mother became paralyzed with nausea and grief as soon as she got on the first plane to the States. It was Wang who lied to the stewardess that her mother’s seat belt was fastened and who held her mother upright as they changed from one plane to the next. In that journey, Wang at seven became her mother’s protector, a role her father was no longer able to assume. He had dwindled and had ““caved-in” during his time in America. His humor had dissolved into fearful caution. “Just remember this, Qian Qian; we are only safe with our own kind.”

When Wang starts school, her father leaves her with a warning, words for her to memorize and repeat, “ I was born here, I have always lived in America.” As an undocumented child of undocumented parents, this serves as her only guidance for twenty-two years. With both parents struggling to make a living, Wang is on her own in an unfamiliar universe, with only a smattering of a new language.

In her Brooklyn elementary school, ESL students are put in a special education classroom. Ignored, Wang turns to books, puzzling out words while using the English alphabet and phonics that her father had taught her in China, back in the days when he still had time for her. Slowly she progresses from Clifford the Big Red Dog to Dr. Seuss and begs her father to arrange for her return to the mainstream classroom that had rejected her months before.

Wang continues to guard and protect her mother, joining her at her sweatshop job after school and becoming her confidant when the two of them are home alone. In turn her mother opens the world of New York to her, taking her to Fifth Avenue to view the holiday windows, bringing a strange old white American into the family who takes them on outings and introduces Wang to the joys of MacDonald’s Happy Meals. Slowly her mother’s confidence grows and blossoms into plans of going back to school and making enough money to hire an immigration lawyer, removing the family from poverty.

In the background, Wang’s father becomes frightening in sporadic episodes, directing his cruelty toward the cat that Wang has managed to bring into the household. “Bad luck,” he says, and when his wife goes into the hospital for surgery, the cat becomes the brunt of his anger. Even when Wang’s mother comes home and grows closer to realizing the ambitions she’s poured out to her daughter, her husband falls into darkness and renewed fear. When his wife divulges her plans, he slaps her in the face, hard enough to leave the mark of his hand unfaded for a long time afterward.

Through all of this violence, turmoil, and chaos, Wang learns, studies, and pushes herself. On her own, she passes the examination process to a school for gifted chidren in Manhattan, in spite of her father’s discouragement and the dismissiveness of the man who has been her teacher. When her mother graduates with a degree in computer science, Wang begins to believe that her own dream of going to Harvard and becoming a lawyer may come true.

“The thread of trauma was woven into every fiber of my family, my childhood,” she says, yet her childhood is heroic and ultimately triumphant. She tells her story without self-pity or drama, dedicating it “To all who live in the shadows: May you one day have no reason to fear the light.” Her memoir is one that should be read by every parent, teacher, and all of us who hide behind our privilege, as an indictment and a wake-up call. Children are being overlooked and under-served in this country. Not all of them have the strength and the determination of Qian Julie Wang.~Janet Brown