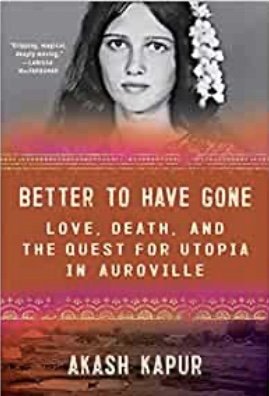

Better to Have Gone: Love, Death and the Quest for Utopia in Auroville by Akash Kapur (Scribner)

History puts Utopia in a bad light. The concept has never worked very well, drenched as it is in failure, death, and tragedy. But what if the effort to achieve the ideal community simply has never been given the time it needs to evolve? The process isn’t pretty, as Akash Kapur shows in his story of “the quest for Utopia” in a barren region of India, but the end result is a town with an international population that thrives in a setting of “vibrant forest.” What was once “a moonscape” is now “a global model of environmental conservation.” But are the results worth the human sacrifice that this achievement demanded?

The “intentional community” of Auroville was born because of the unlikely meeting of three very different people: Sri Aurobindo, a Cambridge-educated Indian mystic, a wealthy French matron, Blanche Alfassa who believes in visions made incarnate, and a young Frenchman who spent his youth in concentration camps. Madame Alfassa recognizes Sri Aurobindo as the Indian seer who came to her in her dreams. She becomes his leading disciple and is known by the name he gives her, The Mother. Bernard, weighted to the breaking point by his years in the death camps, meets The Mother just before Sri Aurobindo dies, putting her at the forefront of the seer’s following. She gives Bernard a new name and, as Satprem, he becomes her primary henchman, propelled by the belief that The Mother is divine.

The Mother has a dream and at the age of 87, she reveals it to the world. She buys 90 acres of barren ground and announces this will become a “Tower of Babel in reverse,” an international community” that will belong “to humanity as a whole.” Three years later, the first settlers arrive, finding an empty desert.

Others join them, from India, Germany, France, Great Britain, and the United States. They become obsessed with finding shelter, water, and food; they dig wells and build huts with their bare hands. They gather seeds that they find within animal droppings and nurture crops of native plants. An administrative group formed by The Mother raises funds and disburses money to Auroville’s inhabitants, who espouse a subsistence economy that has reduced them to peasants. Then The Mother dies and the money begins to trickle away.

Political schisms crack through the utopian surface of Auroville and a form of cultural revolution blazes through the hearts and minds of the residents. Satprem has convinced most of them that The Mother is a divinity and the prevailing belief is she will provide them with what they need. She will heal the sick and bring up the children while the healthy adults work to venerate her memory. Medicine and education are regarded as unnecessary and the energy of Auroville is spent in building a multi-storied edifice that will house The Mother’s spirit.

Within this maelstrom of belief and chaos, two people become the poster children for disaster. A devout member of Auroville, a young Belgian beauty, falls from the heights of the construction project and is permanently paralyzed. The man who loves her, a wealthy patrician from New York who devotes his fortune to Auroville, becomes ill. Both of them refuse the medical help that would save them and they die young, with one survivor.

The woman’s daughter, Auroalice, has known no other world but Auroville. At fourteen she’s semi-educated and semi-feral, having grown up in a tribe of free-range children. She’s adopted by the sister of the wealthy patrician, is taken to live in The Dakota where Lennon and Yoko are her neighbors, and by chance meets a man who had been a childhood friend in Auroville, Akash Kapur. They marry.

Well educated and well off, the two of them live happily in Brooklyn until their pasts begin to claim them. Returning to Auroville with their young sons, they find it’s become a place where they can raise their children safely and happily, as well as a place where their own childhood histories have found peace.

Unsettling and uncomfortable, Better to Have Gone raises troubling questions. Kapur turns to Mao and Robespierre: “Revolution is not a dinner party.” “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.” To create this ecological triumph, people died and children were sacrificed.

Kapur says, “Children of utopias, I’ve come to understand, are like exiles.” He and Auroalice were each rescued in different ways. Kapur’s parents never truly espoused the demands of Auroville; Auroalice became an orphan who was whisked into the wealth of Manhattan after fourteen years of a helter-skelter upbringing. Other children weren’t so fortunate and their stories go untold, “mere expedients on the journey to a new world.”~Janet Brown