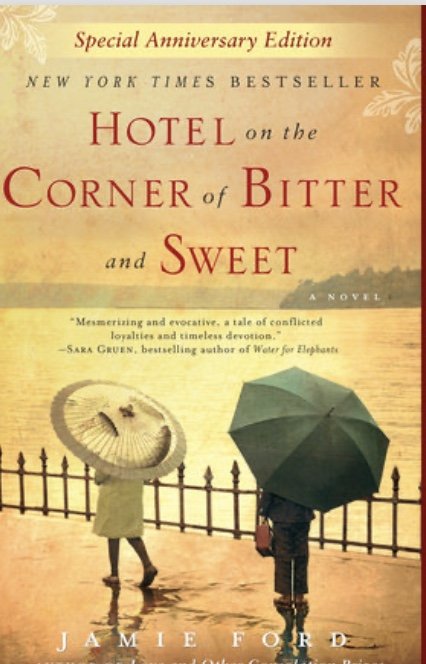

Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet by Jamie Ford (Ballantine Books)

We all need a dash of romance in our reading lives, no matter how cynical we believe ourselves to be. History buffs can read volume after volume of past events but are rarely moved to tears as they turn the pages. Is it important to cry? Yes. Tears are a sign that we’ve moved beyond empathy into sympathy--feeling the same pain. Without that, our understanding is still removed, dispassionate, and easy to forget.

History and romance are a hard combination to unite in literature, since one frequently threatens to submerge the other, but Jamie Ford did it in his debut novel, published thirteen years ago and still in demand. Cleverly juxtaposing past and present, Ford makes the days that began World War II in the U.S. as real as anything we experience today, and he does this through the story of a childhood friendship that becomes a doomed love story--or is it?

Henry Lee and Keiko Okabe are both scholarship students at an exclusive almost all-white school, working together in the school lunchroom. Henry lives in Chinatown, Keiko in Japantown, Nihonmachi. Their two neighborhoods are adjoined but are divided by nationalism, prejudice, and privilege. The Japanese feel superior to the Chinese and the Chinese, like Henry’s father, hate the Japanese for atrocities Japan is committing in Nanjing and other Chinese cities. Even before Pearl Harbor brings the U.S. into war with Japan, Henry leaves his house every day with a badge his father has pinned to his shirt. that says “I am Chinese.”

Born in the same city hospital, Henry is the child of Chinese-born parents while Keiko’s parents were bon in the U.S. Even so, when headlines are filled with Japan’s act of war, Keiko is the one at risk. In Nihonamchi, bonfires in the streets consume anything that will link its residents with Japan. Family treasures are tossed from apartment windows and find their way into the flames. Signs for Mikado Street are replaced with ones with its new name, Dearborn. Japanese-owned businesses that have given economic life to the area are closed or usurped by new owners. Japanese residents from all over the region are rounded up under Executive Order 9066 and are shipped off to internment camps, with almost 10,000 removed from Henry and Keiko’s city alone. When the Okabe family is put on a train and sent to improvised shelters built from cattle stalls in the county fairground, Henry discovers a way to visit Keiko. When her family is transported to Camp Minidoka in another state, Henry finds her. But Henry is only thirteen. His parents bitterly oppose his friendship with a Japanese girl and the two of them lose touch.

Decades later, when Henry is in his fifties, a discovery at the Panama Hotel that was once the pride of Nihonmachi makes headlines. In the basement of this neighborhood landmark are trunks and boxes that had been left in safekeeping when their owners were interned with only the possessions they could carry. As these artifacts are unearthed so are Henry’s memories and as he remembers, a vibrant community that has vanished comes vividly into light.

Ford has based his novel on solid facts. The Panama Hotel that was the sanctuary for jettisoned treasures stands in Seattle’s International District/Chinatown with belongings that were never reclaimed still in its basement. Along with a scant number of businesses and restaurants, this is all that remains of the prosperous community of Nihonmachi that once spread over almost the entire district. Until very recently its history had been forgotten and was given an impetus for revival by the meticulous renovation of the Panama and, in no small part, by Ford’s depiction of the past.

The area has never recovered from the expulsion of its Japanese American residents. After reading Ford’s descriptions of the jazz clubs, the Japanese-owned barber shops, photography studio, the Nippon Kan Theater, the Nichibei Publishing Company, all gone, a walk through the area is tinged with its ghostly past. Passing the historic King Street Station where Amtrak trains whisk passengers across the country, its carefully preserved architecture makes it easy to see the thousands of families being herded onto trains under the guns of soldiers. The cattle stalls of “Camp Harmony” haunt the shadows of the Puyallup Fairgrounds. The sadness of the past is palpable in the present, reawakened by Ford’s story of an interrupted friendship and a shattered community.~Janet Brown