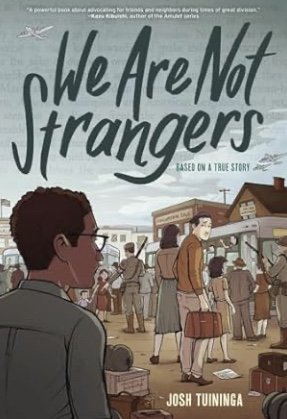

We Are Not Strangers by Josh Tuininga (Abrams Books)

Several years ago I was a guest in a Seattle house that was only a few years away from its one hundredth birthday. My host told me it had been built and owned by one family before he bought it. That family was Japanese and when they were sent to the internment camps, their neighbors made sure their house remained intact and in their legal possession until they were able to return home again.

When I told this story to other Seattle residents, they denied its plausibility. Japanese property was up for grabs after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the resulting incarceration of Japanese Americans in internment camps. The story I was told was a rosy little myth, designed to make Seattle feel less culpable in what was a national disgrace, according to people who were certain they knew the real facts.

And I believed them, until I was given a copy of We Are Not Strangers. Author Josh Tuininga is careful to note this is historical fiction that is based on oral history, written records, and an account told to him by his uncle, whose grandfather had helped his Japanese neighbors during their time in the camps.

His story begins before 1942, when Executive Order 9066 imprisoned over 120,000 Japanese Americans and those who had Japanese ancestry, two-thirds of whom were native born U.S. citizens. The man who was the architect of this order spoke for President Roosevelt when he said “If they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp.”

In the city of Seattle, neighborhoods with racial covenants kept the most coveted parts of the city under white ownership. In an area known as the Central District, people who weren’t considered white made their homes. Sephardic Jews from Spain and the Middle East, known as “Oriental Jews” to many, lived side by side with Japanese families. Members of both ethnic groups who had recently immigrated to the U.S. were denied the right to naturalization by an immigration court and the state of Washington, which was a center of America’s pro-Nazi movement, made the position of Seattle’s Jews a precarious one.

The story of a friendship between two men who share a passion for fishing, a Sephardic Jew and an American-born Nisei Japanese, and the way one of them helps the other to keep his home is given depth and truth by the reproduction of headlines taken from newspapers of that time. Tuininga chose to put his book into the framework of a graphic novel so those headlines scream with the same force they held seventy years ago. Signs that greeted Japanese families when they were finally released from the camps a year after the end of World War II, “Japs Keep Out You Are Not Wanted” and “Japs Keep Moving This Is a White Man’s Neighborhood,” starkly illustrate the terrible hatred that Japanese Americans faced after living under internment for four years. (When the war ended, only 33% of Americans advocated the closing of the internment camps.)

Graphic novels are a robust and illuminating way to convey history. Blending words and art to show shades of emotion and the points of view revealed on the faces of every character makes this form of narrative cinematic and approachable in a way that a conventional novel can’t replicate. Tuininga created both the words and the art, frame by frame, in We Are Not Strangers, supplementing them with historical notes that will come as a revelation to many of his readers. Now more than ever, it’s crucial for us to know what happened in America’s past to keep it from recurring in the future.~Janet Brown