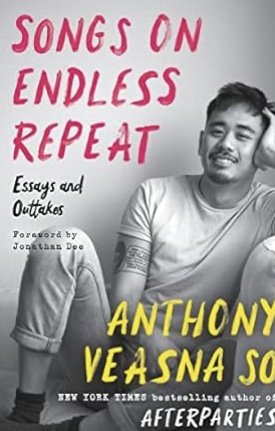

Songs on Endless Repeat by Anthony Veasna So (HarperCollins)

“I have less in common with mainstream Asians, like Chinese, Japanese, the usual suspects, than say middle-aged Jewish people because…both older Jewish folks and young Cambos have parents who either survived or died in a genocide!”

Here is the voice of Anthony Veasna So, who died when he was 28, just months before his book of short stories, Afterparties, (Asia by the Book, August 2021) was published and acclaimed by everyone from the New Yorker to popsugar.com. This offhand line from one of the characters in the recently published posthumous collection of work by So, Songs on Endless Repeat, echoes with absolute truth. The person who would most appreciate and envy that line would now be one of those “older Jewish folks” if he hadn’t, like So, died from a drug overdose--the comedian Lenny Bruce.

So himself took the microphone as a stand-up comedian. He also was a scathing cartoonist, an artist who painted enigmatic self portraits. A writer whose fiction was published in the New Yorker and Granta, he signed a two-book deal with HarperCollins when he was in his mid-twenties. At the time of his death, he was immersed in writing that second book, “a first novel draft [that] will definitely push the limits of digestible length.”

HarperCollins paid $300,000 for Afterparties and for the novel that would follow. Determined to get their money’s worth after So’s death, they scraped together pieces of fiction and nonfiction, tossing it all into the crazy salad that’s become his second—and last—published book. They should never have done this. They looted a grave.

Songs on Endless Repeat is an incoherent mixture of five previously published essays, both in print and online, one lengthy and unpublished piece that delves into reality television, and eight chapters of the first draft that was meant to become his novel, Straight thru Cambotown.

With a stunning lack of respect for this novel that will never be finished, HarperCollins sprinkled its chapters with haphazard abandon among the pieces of nonfiction, as though the portions of what were intended to begin a novel were random short stories. When read as they’re presented on the page, these chapters become staccato. They jangle and chafe. The characters float in a disembodied context, smoking weed, exchanging obscene wisecracks, presided over by a ghostly figure whose funeral is in the offing. They deserve a better showcase than this scattershot presentation, but the only way they’re going to get it is if their readers ignore the nonfiction that gets in their way and encounter each chapter in order, one after the other, as they would when reading a novel. When this way of reading takes place, then the mourning begins. So’s unpolished rush of fiction, his nascent sketches of characters, his tumbled flood of thoughts, all give promise of a book that would have stunned the literary world.

Vinny, Darren, and Molly, cousins whose childless aunt just died in a fiery car crash, are the dead woman’s prospective heirs. Their aunt was the Counter, a leading figure of her Cambodian community. She headed an improvised bank, with members who contributed to, borrowed from, and earned interest from the communal funds. The Counter was the one who collected and distributed the money, while taking her cut, and it’s rumored that she possessed a fortune.

An inheritance from her would be welcomed by the cousins. Molly is back home after an unsuccessful stint as an artist in Manhattan, reluctant to sacrifice her dreams to a lucrative career. Vinny is the lead of the Khmai Khmong Rappers, who spits out rhymes in a mixture of Khmer and English in rhythms that hold his memories of the cadence voiced by Cambodian monks. Darren is making his way through the academic morass of graduate student stipends and applications for fellowships, while his thoughts are still influenced by his days as a stand-up comic, terse and cynical, with a vicious bite.

His is the voice that dominates in these early chapters and his words are the ones that resonate. Describing Cambodian men at family gatherings, he classifies them by what they drink, “Heineken for the humble, Hennessey for the ballers.” A deeper class difference emerges among the men’s children when they reach middle school--are they going to become yellow or brown, choosing academic success or gangster rhythms, “Asian” or “Cambo”? Or will they sink into the mushy definition of Asian American, which Darren derides with his usual scathing insight, “Seriously, we don’t even eat the same grain of rice.”

While Afterparties examined the legacy inherited by the children of those who survived genocide, what’s offered in the opening chapters of So’s unfinished novel is the unwieldy balance between how to succeed in America without jettisoning the cultural roots of the Cambodian community. His final sentences give hints as to how this might have happened for the three cousins, who are forced to immerse themselves in their dead aunt’s livelihood before receiving the inheritance she’s left them. The sketches of Cambotown and its inhabitants give glimpses of a rich and devastating plot that will never come into being, and the sadness of So’s death becomes a matter of literary grief.

But he buries his conclusion among his torrent of words, where it emerges like a polished knife blade flashing in sunlight: “Some things are just lost. So don’t waste your life thinking about it.”~Janet Brown