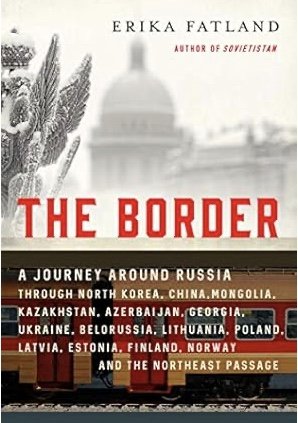

The Border by Erika Fatland, translated by Kari Dickson (Pegasus Books)

Erika Fatland begins her 584-page tome in a spritely fashion that’s as alluring as it is deceptive. Starting at the end of her 259-day journey around the edges of Russia, one that she has spread out over the course of three years, she’s at the edge of Eurasia, where Alaska is only about 50 miles away. She’s concluding a mammoth odyssey along Russia’s border, the longest in the world, extending for almost 38,000 miles along the edge of fourteen countries.

Propelled by the question of what does it mean to have the world’s largest country as your neighbor, Fatland’s final jaunt is on an old Soviet research vessel that will take her through the Northeast Passage. For four weeks she is in the company of 47 other passengers, “a bevy of wrinkly stooped men and women,” all of whom have paid $20,000 to notch up one more exotic destination on their bucket lists. Their conversations consist of travel talk and Fatlander soon learns she’s the only one who hasn’t been to Antarctica. When she tells an 85-year-old Dutchwoman that she’s excited to make a trip in a Zodiac (a rigid, inflatable boat used in rough seas), the response she receives is “Why?’ Her aged companion has been on hundreds of Zodiac excursions and this is a matter of routine for her.

Tracing the journey of the fur trade that gave Russia a firm toehold on the Western part of the US, Fatland vividly recreates the history of explorers and Cossacks, while experiencing dismay at the condition of the islands she visits--”so much rubbish” creating environmental catastrophes. On one of their ports of call, an abandoned cabin bears evidence of a recent occupation. “Mammoth tusk collectors,” she’s told by her guide, “There is a lot of money to be made--we’re talking millions.”

This is the last portion of The Border to reveal humor or any form of delight. Moving swiftly into her time in North Korea, Fatland finds obfuscation, bleakness, and eerie contradictions. In Pyongyang, apartment buildings routinely soar to 20 storeys or more but their elevators are so faulty that residents clamor for spots near the ground floor. A hotel that’s over 1000 feet high dominates the city skyline but has never opened for business. Her guides all carry expensive Chinese mobile phones in a place where coverage to other countries is only available on mountain tops. The DMZ at the division line between North and South Korea holds no human residents while providing “a haven for threatened species.” The beaches in the North are “as beautiful as Vietnam’s” but are devoid of tourists.

On a tour of Chernobyl at one point of her journey, Flatland is disconcerted that it feels “like a package holiday.” Thirty years after the disaster, people still come to a local hospital with dire after-effects. “It takes time for the isotopes to break down,” a senior member of the medical staff says.

Fatland is a historian and this is her focus in The Border. As she makes her way through Asia, the Caucasus, and Europe, there are only vague hints of the current relationship between Russia and its fourteen neighbors. It feels as if she’s writing two separate books, a skimpy travel narrative and an overwhelming torrent of history from past centuries. When she ends her account with time spent in Ukraine, Poland, Finland, and her native country, Norway, history has fully taken over. Not even a camping trip to the final borderline with her father cuts through Erika’s daunting knowledge of the past.

Does she find the answer to her question of what comes with being a neighbor to Russia? Perhaps, but if she did, it’s lost in translation.~Janet Brown