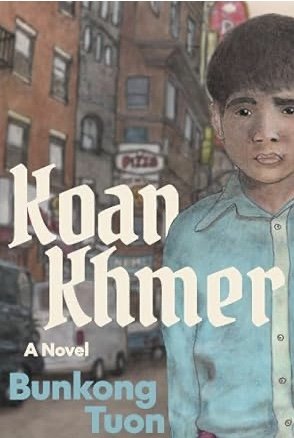

Koan Khmer by Bunkong Tuon (Northwestern University Press)

A little boy and his extended family make their way out of Pol Pot’s Cambodian horror, going from a refugee camp to life in the U.S. where the boy grows up to become a university professor. This affirms that the American Dream is still possible, right? Not according to Samnang Sok, the leading protagonist of Koan Khmer, who asserts at the end of this novel that “my American dream was more of an American nightmare,’ one that didn’t end until after he leaves adolescence.

A child who never knew the date of his true birthday, Samnang’s first memory is of his mother’s death when he was three. Born into a peasant family in a rural village, his Pol Pot years were spent as a naked boy in the woods,” surrounded by the natural world. Although his family were relatively unscathed by the Khmer Rouge, unlike urban, educated Cambodians whose privilege made them targets of Angkar’s rage, Samnang’s uncle and grandparents decided it would be wise to head for the Thai border and the safety of a U.N. refugee camp. The family will live in three different camps before they’re sponsored by an American minister and board a plane for the United States.

At first they’re dazed and delighted by the wonders of a washing machine, a dishwasher, a bathtub, and a television. Then slowly they begin to realize what they’ve lost. Samnang’s uncle is disheartened by the lack of farmland in this small city in Massachusetts. There’s no place for him to fish and he despairs over how he will feed his family.

When Samnang accepts the minister’s invitation to go with him to church, he begins to realize the difference between his family and the parishioners sitting near him on a pew. When the congregation begins to pray, Samnang mutters curses in Khmer under his breath and is later praised for his piety.

Finding an apartment in an Italian neighborhood, the Sok family finds no welcome there. People whose own origins stemmed from immigrants resent the new inhabitants who evoke memories of the Vietnam War. Other boys attack Samnang for being a “gook” and he takes refuge in his schoolwork, gaining English fluency through ESL classes and TV programs. Skipping a grade, he enters high school before he enters puberty, an accomplishment that guarantees he’ll continue to be a social pariah. He stops caring about academic achievements and then stops caring about anything at all. All that he’s found in America is a state of permanent displacement.

What saves him is a chance to move to Long Beach, a city with a large and established Cambodian community. For the first time since his introduction to the U.S he hears his own language, eats his own food, moves among crowds of people who are Khmer. He walks into a library and discovers the poems of Charles Bukowski. He begins to write his own poetry, mining his own experience, and slowly his education begins, with a hunger to learn everything.

It takes years for him to recover from “growing up Cambodian in the 1980s on the East Coast.”

Samnang’s story is “based loosely” on the life of Bunkong Tuon and the stories of his family. The details that unfold in Koan Khmer are often cruel and unsparing: the physical examinations before coming to the US when modest Cambodians stand naked, powerless and humiliated while inspected by doctors; the day Samnang is spat at by a boy while he’s taking a walk with his grandfather who stares in shock at the child’s parents and is met only with a hostile gaze; the terror felt by every Asian in the Los Angeles area when Koreans are attacked during the chaos after the Rodney King verdict. If this is what comes with the American dream, then it’s long past time for us all to wake up.~Janet Brown