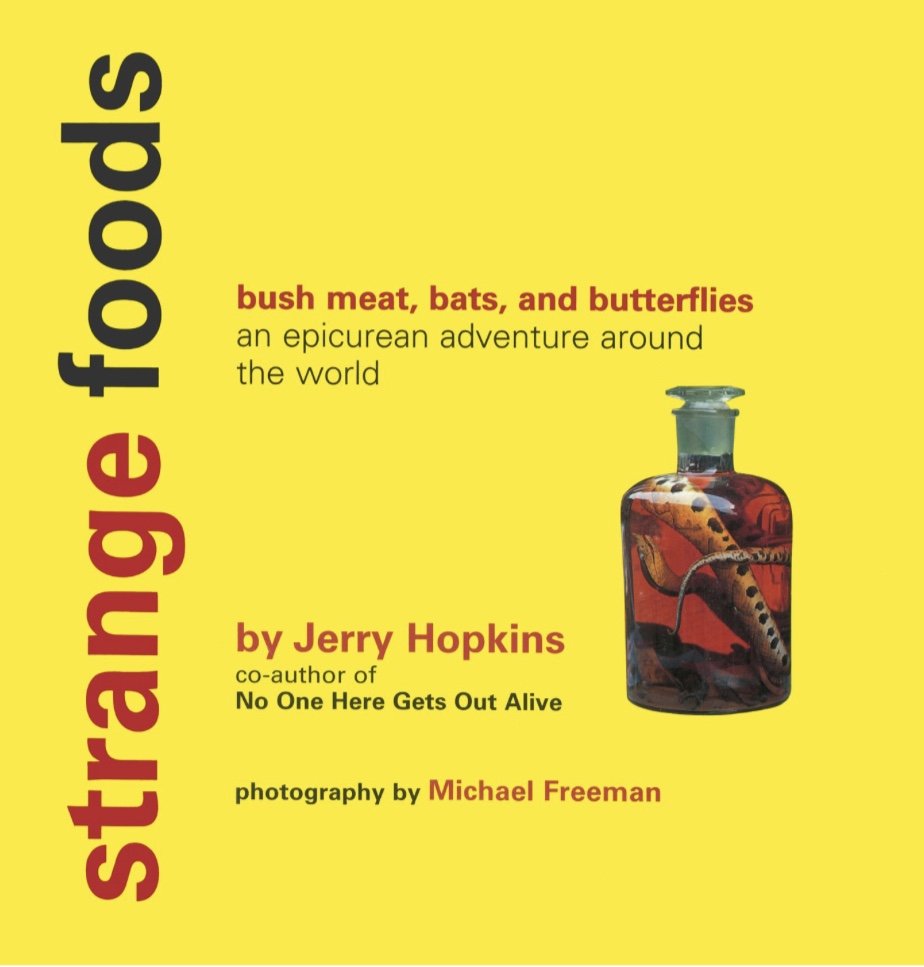

Strange Foods: Bush Meat, Bats, and Butterflies by Jerry Hopkins, photographs by Michael Freeman (Tuttle)

What we think is delicious and what we recoil from as disgusting is determined by our geography, history, and sheer good luck. Nothing points that out like one of the first photographs in the opening pages of Strange Foods. If you think the image of a baby calf on a plate, still in fetal form, is revolting, ask yourself how is that more quelling than a dish made with veal? Would you rather eat a calf that isn’t yet alive or one that’s knocked on the head when it’s a living, breathing, cute little baby? What’s the difference?

That question is posed again and again throughout this provocative book and Jerry Hopkins is the right man to pose it. When his youngest child was born at home, Hopkins refrigerated the expelled placenta, later turning it into a paté for guests at the christening party. Nobody died.

“No one is sure what the first humans ate,” Hopkins says, but it’s a sure thing that they wouldn’t have turned down the dish made of little pink baby mole rats that’s eaten in modern India. Probably the French during the Franco-Prussian War’s Siege of Paris wouldn’t have spurned that either back in 1871, when people flocked to stalls that sold dog and cat meat. Starvation breeds exotic tastes.

Horse meat has been a staple throughout human history, with U.S entrepreneurs in our present day buying wild horses to slaughter and sending their meat to Europe and Japan. Thirty years ago, Seattle’s famous Pike Place Market had a stall selling steaks, roasts, and ground meat that came from mustangs in Montana.

Cows or horses? Both are livestock but only one is commonly raised for food. However in Mexico, when Columbus first showed up, the only domestic livestock raised for human consumption were turkeys and dogs. In the northeast of Thailand, in a distant province where life is rough, dog meat is a staple and, Hopkins reports, in the civilized modern city of Guangzhou dogs and cats wait to be bought, killed, and butchered on the spot—along with deer, pigeons, rabbits, and guinea pigs—”a take-away zoo.”

When mad cow disease emerged in Europe, suddenly kangaroo, ostrich, and zebra appeared on supermarket meat counters as “exotic meat.” Beefalo was a popular meat during a period of soaring U.S beef prices and in Alaska, consumers happily chow down on reindeer sausage, swallowing Rudolph and his colleagues without a qualm. Still, the thought of elephant meat on the menus of African restaurants makes many a Westerner turn pallid.

In the 1970s, muktuk was sold as a snack at an Alaskan state fair. Bits of the skin and blubber from a beluga whale, it was chewy and flavorless, clearly an acquired taste and to the Inuit of Alaska, almost sacramental.

The Arctic offers little in the way of food and whale hunting is still one of the chief means of subsistence. This isn’t necessarily true of Japan, a highly developed country that consumes large amounts of whale meat. It’s indubitably more healthy than more conventional options. “Richer in protein, whale meat has fewer calories than beef or pork, and it is substantially lower in cholesterol.” Whales are rapidly increasing in number around the world, Hopkins reports, and opposition to whaling is decreasing. Who knows? If we can order shark steak in fine dining establishments, will whale be on the menu soon?

Hopkins made his home in Thailand where he lived until his death in 2018. Michael Freeman has spent most of his career in Southeast Asia. The two of them have encountered—and eaten— insects, silk worm larvae, bats, scorpions, and partially-formed chicken embryos still in the shell. They are proponents of a truth that prevails in their book: Anything can be delicious if it meets a kitchen with a clever cook. To back this up, recipes appear in almost every chapter to challenge the squeamish and entice gastronomic adventurers. Rootworm Beetle Dip, anyone? (I don’t know about you, but I’d rather eat that than the classic Scottish meal made from sheep’s stomach and lungs—haggis? No, thanks!)—Janet Brown