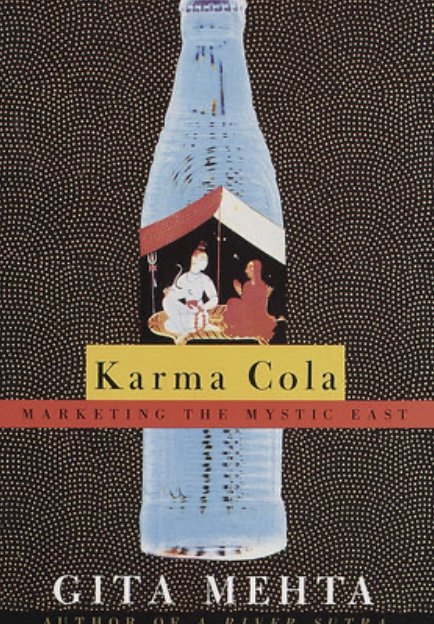

Karma Cola: Marketing the Mystic East by Gita Mehta (Vintage Books) ~Janet Brown

Blame it on the Beatles. When they found their popularity was beginning to fade as the Rolling Stones climbed to the top of the sex, drugs, and rock and roll pantheon, they turned to the mystical world of India. “The kings of rock and roll abdicated. To Ravi Shankar and the Maharishi.” Meditation, gurus, and sitars became cool and India became the new Mecca for hip westerners. While those who couldn’t afford the plane fare took refuge in reading Siddhartha and listening to “raga rock” with its tabla and sitar influences, the more adventurous and affluent descended upon the Subcontinent, looking for whatever enlightenment might descend upon them there.

Suddenly pseudo-Hindus took their place among the Europeans who had traveled the latest version of the Silk Road in search of cheap drugs. The two forms of quests collided and merged, providing a convenient source of revenue for Indian entrepreneurs on every economic level. “From accepting the fantasies it was a very short haul to…manufacturing them.” Mysticism became “a home industry,” supplied to hordes of Westerners who were fleeing materialism and wanted to experience the spiritual cleansing of poverty.

A French diplomat claimed that 230,000 of his country’s citizens had arrived in India by the 1970’s, with at least another 20,000 who were there without proper documentation. Their numbers were swelled by other Europeans, Americans, Australians, and Canadians, “in pursuit of either mind expansion or obscure salvations.”

Jung had arrived long before this influx and correctly assessed the risks of becoming an expat in India, saying that India was the essence of naked realty while the West was cushioned by “a madhouse of abstractions.” Without that cushion, Westerners would “disintegrate in India.”

Gita Mehta, born in Delhi, educated at Cambridge, a documentary filmmaker and a war correspondent for NBC who covered the war in Bangladesh, was fascinated and amused by this influx of privileged Westerners who eagerly gave up all privileges in search of whatever truth was offered to them. Mehta, herself a product of privilege, brought her cynicism and sharp wit to what she termed “entering a haunted house on a dare,” an ashram in Poona where God presides. His future successor is embodied in a smaller God, a Swiss five-year-old who runs in feral splendor with the neglected offspring of the acolytes. Two thousand followers give all their attention to absorbing God’s wisdom, taking on Hindu names that they’re unable to pronounce properly.

“Sacred knowledge in the hands of fools destroys,” Mehta quotes from the Upanishads. She’s told by a young woman who left India in a state of diagnosed insanity, “I should never have trusted gurus who wear Adidas running shoes.” Others happily divulge their past lives to her--”the Buddha’s charioteer,” claims a woman who in another realm of existence was the mother of her own husband. A young French woman who still nurses a daughter who boasts a full set of teeth, idly speculates that she could become the next Mother of the utopian world of Auroville, since she and the present leader share a nationality--”famous, like a Pope!” In the sacred city of Benares, spiritual enlightenment is enhanced by hypodermic needles. “Everywhere now,” Mehta is told by a German photographer, “you find morphine.”

Mehta’s breezy gallows humor and anecdotal narrative may lead to questions of exaggerated quasi-fiction. However everything she’s written in Karma Cola is backed up by Akash Kapur’s Better to Have Gone (Asia by the Book, 3/24/2022). He and his wife both grew up in Auroville as its utopia was being formed. His account of this community is as harrowing as Mehta’s depiction of 20th century enlightenment. Even so, he and his family have returned to what seems to have become a successful experiment, embodying every goal longed for by the spiritual seekers whom Mehta has pilloried. This may be the ideal conclusion to her satirical dissection--that a new city has been created in India, one that flouts every form of Indian reality that the spiritual seekers once embraced.