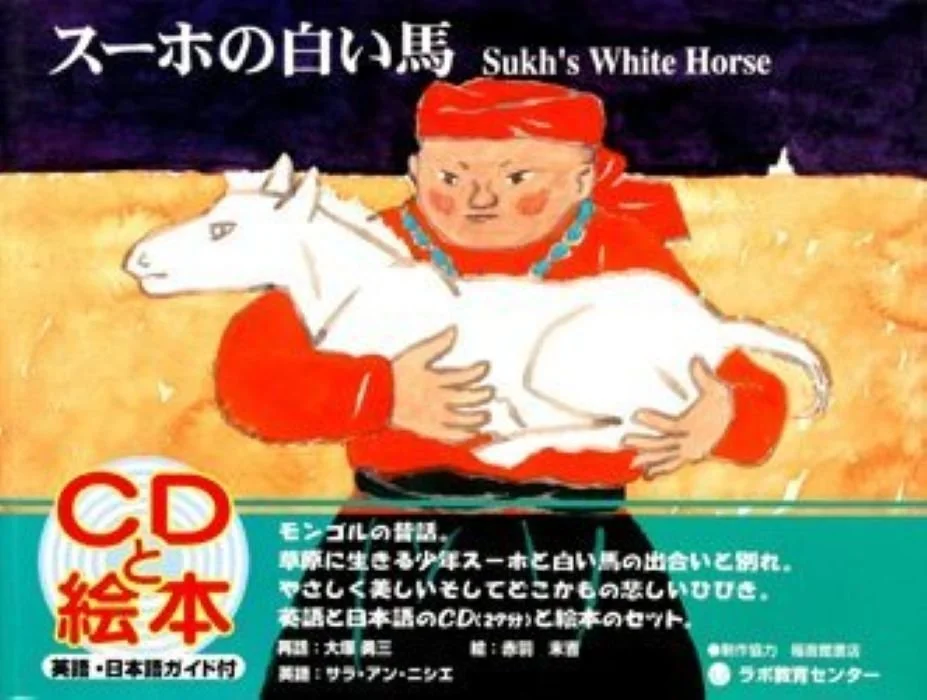

Sukh's White Horse retold by Yuzo Otsuka, English text by Sarah Ann Nishie (Labo Teaching Information Center, Tokyo) ~Ernie Hoyt

Sukh’s White Horse is a Mongolian folktale. I believe one of the best ways to learn about another country’s culture is by reading or listening to their folktales. In this tale, the story focuses on the origin of a musical instrument called the morin khuur or horsehead fiddle. It is retold by Yuzo Otsuka and was translated into English by Sarah Ann Nishie. It is illustrated by Suekichi Akaba.

The morin khuur is a Mongolian stringed instrument. It is one of Mongolia’s most significant cultural heritage items. In 2001, UNESCO (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization) designated the morin khuur as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

The morin khuur or horsehead fiddle is so called because the upper part of the instrument is shaped like a horse’s head. This book tells the story of how the instrument was invented

As with most fairytales and folk tales, the story starts long, long ago. On the plains of Mongolia lived a shepherd boy called Sukh. He lived with his grandmother. It was just the two of them. He worked as hard as any adult - he got up early in the morning and helped his grandmother cook breakfast, then he would take their more than twenty sheep out onto the plains.

Sukh was known for his great singing voice. He was often asked by other shepherds to sing for them. “His beautiful singing voice would ring out across the plain and far into the distance”.

One day, Sukh did not come home. It was already dark. His grandmother became very worried about him. Even the other shepherds started to wonder what happened to him. They were all distraught and wondering what they should do when Sukh came running home holding something white in his arms. It was a foal.

Sukh took care of the foal which grew into a beautiful white horse. Sukh loved this horse with all of his heart. One night Sukh woke up to hear his horse in distress. When he went to check, he saw the horse trying to protect his herd of sheep from a big wolf. Sukh was so grateful to the horse for protecting his herd.

During the spring of one year, the noyon, or local ruler, was having a horse race in town. He said the winner would get to marry his daughters. Sukh’s fellow shepherds told him he should join the race. Sukh decided to join the race and he won!

However, when the noyon saw that the rider of the white horse was a poor shepherd, he reneged on his promise to give his daughter away in marriage and gave Sukh three pieces of silver and told him to leave the white horse as well.

Sukh got angry and yelled back at the King, “I came to race, not to sell him”. This made the King angry. He ordered his men to attack and beat Sukh and also took Sukh’s white horse away. Sukh’s friends managed to get him home and with the help of his grandmother, he eventually recovered. Unfortunately, he was still suffering from the loss of his white horse.

The noyon was so proud of the horse that he wanted to show it off to everyone. He had a party and was planning to ride the horse in front of everyone for the first time at the party. He had his men bring the horse and mounted the horse.

Then it happened - “The white horse leaped up with fearsome energy. The ruler rolled off of him, down onto the ground. The white shore shook the reins out of his hands and began to run like the wind through the screeching crowd”.

The noyon was furious. He ordered his men to catch the horse. Or if they couldn’t catch him, then shoot him to death. The white horse had run back to Sukh with its body full of arrows. Sukh tried to save the horse but alas, it was to no avail. The next day the horse died.

For many nights, Sukh couldn’t sleep. When he finally did fall asleep, he had a dream. In the dream the horse spoke to him softly. The horse said, “Don’t mourn so. It would be better to make a musical instrument out of my bones, hide, sinews and hair. That way, I can always be beside you. I can comfort you”.

The next day Sukh began to work on making the instrument, following the instructions from the horse in his dreams. When the musical instrument was finished - it was the birth of the morin khuur.

Once you finish reading the story, you can enjoy listening to the story again in English and Japanese on the CD that comes with the book. The CD also includes a bit of background music with sounds from the morin khuur.

The story is sad but uplifting at the same time. It’s a story of love and trust between a boy and his horse. It always strikes me as rather strange why many folktales have tragic endings. I for one, would like to know what happened to the noyon after the horse threw him off.