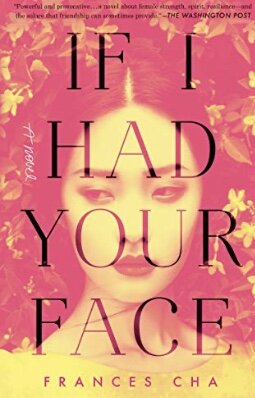

If I Had Your Face by Frances Cha (Ballantine Books)

The quest for beauty and the hunger for family dominate the lives of five young women who live within the same building in Seoul’s famous Gangnam neighborhood.

Ajuri, who lost her voice in a childhood fight with schoolmates, earns her living in a hair salon, making other women beautiful. Her roommate and childhood friend, Sujin, calls her “the little mermaid,” who communicates solely with pen, paper, and the gift of touch. Without speech, Ajuri has sharpened her other senses beyond what they had been before she became mute; “the wind,” she says, “I don’t remember it having so many shades of sound.”

Sujin and Miho grew up together in the same orphanage. Their lives diverged when Miho’s artistic talent took her to live for years in Manhattan. When she returns to Seoul, Sujin urges her to live in the “office-tel” building,” with its desirable zip code and proximity to the subway. Miho, seeing this as a place “for the unfettered”, becomes roommates with a stranger, Kyuri.

Kyuri works in one of Seoul’s most prestigious “room salons,” one that is known as a “10 percent,” employing only the prettiest 10 percent of the girls who make conversation and pour drinks for men who “pay to act as bloated kings.” “Electrically beautiful,” Ajuri describes her neighbor, while Miho sees her as “painfully plastic.” Kyuri has paid a borrowed fortune for her skin that “gleams like pure glass” and her features that have been sculpted into a replica of a popular Korean singer. Trapped in debt, she is haunted by her “expiration date” and thinks of moving to Hong Kong or New York, where beauty is measured by a less demanding standard.

Sujin yearns for Kyuri’s face and the chance it will give her to become a room salon girl, even though she knows it will take at least six months for her to recover from the surgery. The reshaping is a brutal process that makes Sujin mask her lower face to hide the swelling and the numbness that makes her drool as though she was shot up with novocain. But when her beauty begins to bloom, she claims the happiness that eludes Kyuri.

These girls are the reason why a young wife decides to move into the office-tel. She’s magnetized by the glimpses she sees of their closeness and their freedom, an intimacy and mobility that she’s never had. Wonna, after a long series of miscarriages, guards her most recent pregnancy with fierce possessiveness, yearning for the daughter who will give her a family of her own.

Within the framework of these lives, Frances Cha gives a view of modern Korean life with the perspective of an American outsider and the trained eye of a professional journalist. She shows the extraordinary wealth and power of Korea’s upper class in a single sentence, when an heiress approached by a stranger on the street, says to her companion, “Maybe I can have him killed.” “Korea is the size of a fishbowl,” Miho observes, “Someone is always looking down on someone else.” Economic class is difficult to transcend, which makes beauty a necessity.

But beauty gives a fleeting advantage, accompanied by a crippling loan that’s taken on with little thought. “It is easy to leap when you have no choice,” Kyuri remarks.

Many women face the prospect of old age without children who will provide emotional and financial support. Korean firms offer maternity leaves that can last at least for three months and as long as a year, something they do their best to avoid providing. The cost of bringing up a child can be astronomical. Parents who don’t qualify for free government daycare can end up paying huge amounts for child care. Peer pressure makes them buy budget-draining robots who read aloud to children from books that come in sets of 30-50, air purifiers for gigantic baby-strollers, and “pastel bumper beds with tents.” “All these ob-gyns and birthing centers and post-partum centers are going out of business because nobody is having children.” Kyuri says. Meanwhile hospitals devoted to cosmetic surgery attract patients from all over the world and a never-ending supply of room salon girls.

Artifice, for Cha’s characters, is an established fact of life. Elaborate weddings with hundreds of guests confer a fragile status upon wives who wait for husbands to come home from the girls in room salons. Cha strips away myths that proclaim the strength of family and the privileges of beauty, revealing a glittering, lonely world where women learn to support each other.~Janet Brown